THE YAKSHAS, NAGAS AND OTHER REGIONAL CULTS OF

MATHURA

The architectural remains from Mathura

discussed, are a good indicator of the scale of organisation and popularity of

the multiple religious cults that existed in the region, but there were

possibly many other local sects and practices that flourished around the region

that did not have any monumental architecture associated with them. The cult of

the numerous Yakshas and the local village gods and goddesses are some of them,

and yet their popularity in the region rivalled the major sects like Buddhism

and Jainism at Mathura.

This blog, The Second Part of – “ THE NAGAS :

THE ORIGINAL RULERS OF INDIA” is a continuation from the earlier Blog and here

we discuss these popular cults of the region and their representation in the

sculptural imagery at Mathura. The repertoire of Naga and Yaksha imagery at

Mathura is extremely diverse, and they occur both as independent cults in their

own right, displaying certain iconographic conventions as is discerned from the

sculptural evidence, or as part of the larger Buddhist and Jaina pantheons, in

which they are accorded a variety of roles and are depicted variously. An

interesting fact to note is that these regional cults are dispersed quite

evenly in the region, and run parallel to most of the Buddhist and Jaina

sculptures. The beginnings of these cults can be traced back to the 2nd

century B.C.E, as exemplified by the colossal Parkham Yaksha, or perhaps even

earlier if one takes into account the various terracotta figurines that occur

as early as 400 B.C.E. They not only coexist and flourish in Mathura, along

with the many other religious sects, but also perhaps outlive the latter,

continuing to be an inevitable part of the local beliefs and practices of the

region in the present times. Religion in itself operates at different levels.

ranging from large scale dominant sects like Buddhist, Jaina and Brahmanical

ones, to the local and region specific gods and goddesses, Yakshas and Nagas,

along with the worship of and offerings made to domestic household deities. All

of these aspects arc amply reflected in the archaeological and epigraphic

evidence from Mathura.

Yakshas, Yakshis and other Demi-Goddesses of

Mathura

Commenting upon the research done on the

antiquity and development of the cult of the Yaksha in Indian art and

mythology, with special reference to the site of Mathura, G. Mitterwallner

emphasises that although there has been a lot of investigations done by known

scholars on the Yakshas of ancient India, there has been absolutely no work

done on the Yakshas of specific sites or cities so far, Mathura being one of

them.

The first comprehensive analysis on the Yakshas

was done by Ananda Coomaraswamy , who traced the development of the cult of the

Yakshas using a combination of literary and sculptural data. He discusses the

'Aryan as well as the Aryan elements in the evolution of the iconography and

religious history of the cult'.

His sources range from the Vedic texts, to the

Pali Buddhist and Jaina literature, along with the archaeological evidence

suggestive of the development of the cult. Discussing the multivalent attitude

towards the Yakshas, he debates both the benevolent and the malevolent aspects

of these deities as reflected in the literary texts, invoking fear at some

times and respect at others. Coomaraswamy discusses the antiquity of the cult,

stressing the various ways in which these gods were worshipped and enshrined,

at the same time undertaking a discussion on the cult of popular Yakshas, like

Naigamesha and Kubera that are represented independently, as well as occur as a

part of other religious pantheons like in Buddhist and Jaina ones. Interpreting

the use of the Yakshis as an artistic motifin Indian art, Coomaraswamy

underlines the deeper association of the Yakshas with the water cosmology

derived from the philosophic discussions of the Upanishads. Therefore, what may

appear to be representing a mere tutelary deity or an ornamental motif has in essence,

a deeper philosophical importance that is well represented in the ancient

Indian texts.

Tracing the development of the Yaksha cult in

the plastic arts of ancient India, Coomaraswamy points out to the antiquity of

the imagery of Yakshas, and sees them as precursors to the life size Buddha

images that were later modelled on the same pattern as those of the Yaksha

images, the artists drawing inspiration from the latter. This hypothesis has

been widely accepted in the scholarly circles, especially in context of Mathura,

where the Greco Roman influence is seen to have played an important role in the

development of the Mathura school of sculpture. Arguing against this contention

Coomaraswamy, along with other scholars like Vincent Smith and Growse, argue

for the indigenous development of the Mathura School, taking the pot bellied

Yaksha figures from Mathura as proto types after which the Buddha images in the

region were fashioned. Coomaraswamy therefore concludes, that this being the

case, it is not unlikely that Mathura would have produced the first Buddha

images and not Gandhara.

Reverting to our discussions on the Yakshas from

Mathura, it is observed that they can be divided into two broad categories,

i.e. either represented as free standing or seated figures carved in round, or

relief, that would have served as independent cult images, the second are the

Yakshas that occurred either as guardian deities or attended some worshipped

personage or cult emblems. The latter are especially seen in the case of Buddhist

and Jaina iconography, where they occur as attendants to the images of the Buddha, Bodhisattvas or the Jaina tirthankaras,

or are at times depicted as worshipping cult symbols like the dharma chakra,

stupas, etc. A third category can also be identified, which comprises of the

use of the imagery of the beautiful voluptuous Yakshis as ornamental motifs

depicted primarily on the railing pillars from Mathura. Here , we would like to

enumerate a few examples of each category from the various sites of Mathura.

The potbellied crouching dwarfs are the most

common representations of the seated Yaksha figures. In most cases the knee is

fastened to the belly with the help of a scarf, the facial features are

demonic, with earrings and necklaces forming a part of the ornamentation. In

some cases the arms of such Yakshas are seen as supporting a huge bowl,

resembling the Atlantes figures. In other instances these figures are depicted

with grotesque facial features and conspicuous genital.

The second most common representation of a seated

male Yaksha is one of a pot bellied male figure, squat-legged with a cup in one

hand and a money purse in the other.

These figures are often identified as

representing the god Kubera, and sometimes are depicted with a seated female

figure alongside, which may be taken to represent the goddess Hariti. Both are

assumed to fulfil fertility functions and worshipped independently in their own

right as well, apart from forming a part of Buddhist and Jaina iconography.

However, scholars have not been consistence with the identification of Kubera

images. The catalogues of the Mathura Museum by Vogel and Agrawala, exhibit these

inconsistencies, where in some cases such potbellied figures are identified as Kubera,

while in the others they are just termed as Yaksha figures. It may be noted

that in most of the Yaksha and Yakshi figures there are no inscriptions that

may facilitate their identification, or provide names of these gods and

goddesses. In some cases though, the identification of the Kubera and Hariti

images are possible. with a fair amount of certainty, especially where the

former is depicted with a mongoose and a goblet, two icons unmistakably

associated with Kubera, and the latter is depicted holding a child in her lap.

The hands in most of these sculptures are raised in Abhayamudra, and at times

Kubera is depicted with other religious icons as well like the dharma chakra.

In an interesting example of artistic improvisation from Mathura, Kubera is

depicted as being seated in Bhadrasana playing the harp, while Hariti is seated,

holding out her hand in Abhayamudra. Sometimes both the divinities are

surrounded by figures of devotees with folded hands paying their respects to

the gods.

Yet another category of male Yakshas can be

identified form Mathura, in most cases these Yakshas hold indistinct objects in

their hands, in one specimen a Varah faced Yaksha is seen as holding a long

necked bottle and a basket containing a garland, in another image the Yaksha is

seen holding a club and a vase. Other miscellaneous figures are depicted with

carrying various objects, like a trident or even a ram's head as depicted in

one particular specimen.

Aside from these individual specimens carved in

the round, there are many Yakshas that are depicted on bas-reliefs and that

form a part of the monumental architecture at Mathura. The most common ones are

depiction of the dwarf figures from the railing pillars and the bas-reliefs,

that show them crouched prostrate, with a standing female figure on their back.

Other dwarf figures occur on miscellaneous architectural pieces like doorjambs

and architraves, depicted as being pot bellied and with a grotesque facial

expression, and these fulfil the role of being attendant figures carrying

baskets with flowers and other offerings or at times with flywhisks in their

hands. There is only one representation of a Yaksha occurring independently on

a bas-relief, belonging to the Kushana period, which shows the figure wielding

a musala in his left hand, identified as Moggarpani Yaksha by Agrawala.

A distinct category of Yakshas from Mathura

depicts them as supporters of architectural parts or of bowls. The Yaksha

atlantes and some representations of them supporting the dharma chakra have

been mentioned. A large number of bowl supporting Yakshas have also come to

light from different sites in Mathura. The figures from Palikhera and

Govindnagar, being perfect examples of these. The stone bowl from Palikhera is

inscribed and is dedicated to the Buddhist sub-sect of the Mahasangikas.

Similar specimens have been further discovered

from Govindnagar, the best preserved specimen depicts a Yaksha carved in the

round, supporting a broken bowl on its head. The ornamentation on the figure

consists of a torque and earrings, and the facial expressions and the general

countenance deceives the figure for a female. There have been speculations

about the exact role that these bowl supporting Yakshas played.

Comparing the Mathura specimens with similar

examples from Amravati, Vogel mentions that many reliefs from the latter site,

feature a pair of bowl supporting dwarf Yakshas, which are placed at either

side of the entrance to the ambulatory path around the stupa. In many of the

sculptures male and female devotees are depicted as making offerings in these

bowl or else taking something out of them. On the basis of this it has been

concluded that similar Yakshas from Mathura too fulfilled the same

function-that they were placed at the entrance to a sacred stupa spot and

served as a bowl stand for offerings. This further conformed with their role of

a gatekeeper, a role that is normally assigned to a lot of Yaksas has when

associated with Buddhist and Jaina iconography.

Moving to the female counterparts, sculptural

representation of Yakshis from Mathura is overwhelming. The freestanding specimens

could have represented some local goddesses worshipped by the people. The other

female figures form a part of the architectural sculpture and are artistic

masterpieces. These figures are beautifully carved, depicted in various graceful

poses, and are mostly used as decorative motifs for the ancient buildings. The

standing or seated squatting female figures, mostly depicted with a child on

the lap, hands raised in Abhayamudra are identified as goddess Hariti. They occur

independently or with a similar seated male Yaksha figure, usually identified

with Kubera. The Kubera and Hariti figures depicted together in relief are

found in large numbers from Mathura.

The other categories of female Yakshis, depicted

on the architectural sculpture, occur in various poses. The Mathura artists

seemed particularly fond of depicting the shalabhanjika figures on the railing

pillars and reliefs. In most of these specimens, the female figure is depicted

in a graceful attitude, standing on a prostrate dwarf under a tree, with one

hand clasping a branch, while the other resting on the hip. Most of these

figures are depicted nude, but for the heavy girdle and the usual ornaments

like an elaborate headdress and necklaces and anklets. Other than the

shalabhanjika, the figures are sculpted in various other attitudes, like that

of loosening their girdles, or feeding a parrot, holding a stalk of flower,

holding a dagger etc.

An important category of female figures from

Mathura is the various matrika plaques that are found from the various sites in

the region. A lot of these plaques are from the site of Plaikhera that depict

these goddesses seated or standing in various poses. The number of female

figures depicted is not standardised and the number varies from two to seven.

Agrawala identifies these as depicting the cult of the saptamatrika or seven

mother goddesses, each of them identified with their characteristic emblems.

Most of these plaques belong to the Kushana period where the number of

goddesses depicted on a plaque does not seem to be standardised, but was

elastic and depended on the discretion of the artist or the patron

commissioning the sculpture. There are also a number of images of the goddess

Vasundhara, identified with ajar and the fish symbol, that are found from sites

like Palikhera and Bajna from Mathura. N.P. Joshi cataloguing these matrika plaques

from Mathura has classified them into various categories. Defining what would

really qualify as depicting a matrika in a plaque, he clarifies that female

figures with one child or two or more children are generally known as Mothers

or Matrikas and these are found in large number in Mathura, fashioned both in

stone as well as terracotta.

Further he identifies 13 broad categories in

them that roughly include women with human figures, standing or seated,

depicted with a child, matrikas with animal or bird faces with children, some

of the female figure holding a child are depicted together with Kubera, while

others are standing in a line without any children depicted. Joshi also points

out that none of the female figures are depicted with any weapons or with any

mount, an opinion that can be contested, when one considers the saptamatrika

plaque that is catalogued by Agrawala, which clearly depict each goddess with

her respective weapon and mount.

Apart from these matrika figures are also the

depiction of Brahmanical goddesses like Lakshmi, Vasundhara and the goddess

Durga in her Mahisasurmardini form. The Mahisasurmardini images are also

fashioned in Mathura in large numbers and it seems that the goddess was

worshipped popularly in the region. The earliest specimens of the Mahisasurmardini

plaques occur from the Kushana period and are fashioned in terracotta (Sonkh).

As for the geographical distribution of the

Yaksha and the other goddess images, they are to be found all over the region

of Mathura. The widespread distribution of these matrika sculptures is

acknowledged by Joshi, and the sites he mentions that have yielded these

sculptures are:

Manoharpura-Mathura City

Girdharpur

Nagla Jhinga

Potra Kund, Katra

Kankali Tila

Ral Bhadar

Palikhera

Sitala Paisa

Bajna

Dhangaon

Rani ki Mandi

Brindaban

Tayyapur

Arjunpura

Bhuteshvar

Kervi Village

Naya Village

Usphar

Mahaban

Kevala Village

Akrur Village

Considering the fact that some of the sites like

Jamalpur and Katra were considered as primary Buddhist strongholds in the

Kushana period, and similarly the site of Kankali was a Jaina site, Joshi

concludes that the find spots of various matrika figures indicate that the

matrika cult was basically an important popular cult accepted by the Buddhist,

Jainas and the followers of the Brahmanical faith, and that the entire region

was under its influence?

Collating the epigraphic evidence from Mathura

to these images, it may be observed that unlike the Buddhist and Jaina statues,

hardly any of the Yaksha, Yakshi or goddess sculptures were inscribed. There

are only a handful of examples where these statues are inscribed with specific

names of the deities mentioned, or that the donors have engraved their names

and the nature of their donation, a practice that is otherwise common to the

Buddhist and Jaina imagery from Mathura. The inscription from the site of

Nagala Jhinga, only the reading of which is available, dated to the 2nd century

B.C.E, records the setting up of a statue by a person by the name of Naka, who

identifies himself as being the pupil of a certain Kunika. The Yaksha image

from the site of Parkham is also inscribed, dating to 2nd century B.C.E, here

the sculptor again identifies himself to be the pupil of Kunika, probably the

same person as mentioned in the inscription from Nagala Jhinga, as both the

inscription are contemporaneous in date. The Yaksha itself is referred to as

the' Holy One' and no name is offered in the inscription of the deity. There

are also the finds of a Kubera sculpture and a female statue from the site of

Parkham, but the inscriptions on the pedestal of both these images are damaged

and no sense can be discerned from them. The site of Gayatri Tila has yielded a

statue of a pot bellied male figure attended by two standing females, the

sculpture being inscribed with a donative inscription, but due to the damaged

condition of the sculpture, only the names of the donors are preserved, and the

Yaksha represented by the sculpture cannot be identified.

Another similar example is from the site of Ral

Bhadar, where an inscribed sculptured plaque, depict a seated male and female

figure, but only the concluding part of the donative inscription is preserved.

Similarly the site of Mora, apart from yielding remains of a Bhagvata temple,

has also yielded two inscribed statues of female figures, probably some

Yakshis, the statues of whom are commissioned to be made at the site by the

devotees.

The Naga Divinities at Mathura

As early as the 1880' s, Growse published a hand

copy of an inscription he found from the site of Jamalpur that provided

tangible proof to the existence of a Naga sanctuary at the site. The

inscription incised on a stone slab read 'the place sacred to the divine lord

of Nagas Dadhikarna' . The inscription proved that the site of Jamalpur was

probably associated with the worship of the Naga divinity by the name of

Dhadhikarna, and that the latter had a temple structure of its own there, perhaps

before the establishment of the Huvishka vihara at the site. This was further

confirmed by another inscription that came to light from the site, incised on a

pillar base donated to the Huvishka vihara, it was a gift from Devila, 'a

servant of the shrine of Dhadhikarna'. This apart from proving the historicity

of the Naga cult at the site also confirmed that the shrine of the Naga lord Dhadhikarna

and the Buddhist viharas coexisted and were contemporaneous to each other.

This was only the beginning to the finds of Naga

sculptures from Mathura. In 1908 Pt. Radha Krishna acquired a life size image

of a Naga, from the village of Chhargaon. The hooded Naga statue depicts the

deity with its right arm raised over the head ready to strike. The figure wears

a dhoti and an upper garment, and a necklace for ornamentation. The head is

surmounted by a seven-headed snake hood. The inscription on the back of the

sculpture, records the setting up of this image by two individuals during the

reign of the Kushana king Huvishka. The Chhargaon image seemed to have to some

extent provided a fixed iconographic convention for the freestanding Naga

images from Mathura, as several similar specimens were discovered from around

the region.

Growse discovered a Naga statue from the Tehsil

of Sadabad, which was in a better state of preservation than the Chhargaon

image, with the cup held in the left hand very distinctly, and the head as

usual surmounted by the seven-hooded canopy.

Another Naga statue came from the village of

Khamini, which can be stylistically ascribed to the Kushana period, and yet

another that was purchased from the shrine of Dauji in the present day Mathura

City, which was salvaged for worship by the local priest, and was enshrined as

Balrama in the temple at the site. From the inscription on the image it was

determined that it belonged to the Kushana period, and was only twelve years

later in date than the Chhargaon Naga. The continuity of Naga worship in the

succeeding Gupta period is ascertained by a Naga sculpture that was obtained

from somewhere between the villages of Maholi and Usphar, and the fragment

consisted of the hind portion of a coiled up snake carved in the round. The

roughly dressed base contained a Sanskrit inscription in two lines, ascribable

to around the 3rd century . recording the donation of the image. The owner of

the image had made a mud effigy on top of the image, which was explained, to

the visiting pilgrims as the popular legend of Lord Krishna subduing the Kaliya

Naga.

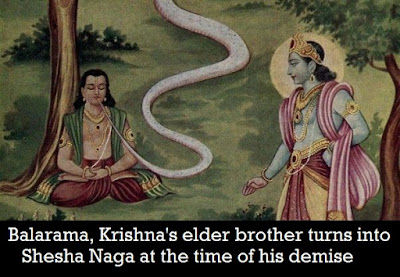

Scholars have emphasized a close association of the

Balrama cult of present day Mathura, with the Naga worship in the ancient past.

In fact it is no coincidence that the present day Balrama images are largely

fashioned after the Chhargaon Naga image.

Vogel has highlighted that the modern day white

marble images of Baladev, fashioned in Mathura, are stylistically, descendants

of the Chhargaon images with a few iconographic changes. The snake hood, in

accordance to the mythical legend of Balrama, is seen to represent the fact

that Baladeva was the incarnation of Naga Sesha, and the cup in the left hand

is indicative of the drinking propensities of the deity. Vogel goes on to

conjecture that perhaps the mythical personage of Balrama was developed from

the Naga lord, and if this being the case, one can trace the historical development

of the Naga Balrama in the region, which later became absorbed into the

Krishnaite pantheon. The Buddhist and the Jainas also to some extent sought to

adapt the popular worship of the Nagas into their religion. The Nagas in

Buddhist and Jaina iconography are depicted as devotees of Lord Buddha and the

Naga hood forms the headgear of the Jaina tirthankara Parshavanath.

The Nagas in the Krishna legend are depicted in

two ways--one is the Naga association with Balrama, who in Vaishnava mythology

is the older brother of Krishna, and second is the ultimate triumph of the

Vaishnava cult over the local Naga deities and their absorption into the larger

Vaishnava religion. The most popular perception, and the one that is supported

by the Epic and Puranic literature, is the association of the Naga with

Balrama, who in the Epics is depicted as the older brother of Krishna. The

Mahabharata and the Harivamsa Purana, both have preserved elaborately the

legends of Krishna and Balrama, being born in the environs of Mathura, and

therefore are inseparably linked to the region. Along with Krishna, Balrama is

also seen as a form of Vishnu, and an incarnation of the serpent lord Sesha.

Balarama is also closely associated with drinking and intoxicants , and in some

legends is also seen as an agricultural deity.

The parallels of this latter aspect, of Balarama

being an agricultural deity, are also traced to the ancient Nagas, who were

closely connected with water--the element all-important for agriculture. These

two attributes use of intoxicants and the association with agriculture-have

shaped the iconography of the Balrama images in which he is depicted as a Naga

deity holding a cup in this left hand and a plough over his shoulder.

N.P. Joshi , concentrating his study on the

iconography of Balarama images, using a combination of literary and sculptural

evidence, perceives the Naga worship in India as primarily a folk cult and

opines that the theory that Balrama as an incarnation of Vishnu might have .got

further impetus from the followers of the Naga cult because it conferred a

superior status on their deity. He stresses that from Kautilya's Arthasastra,

it is evident that Naga worship was extremely popular in Mauryan times and that

is amply depicted from the sculpted panels of Bharhut, Sanci and Amravati. The

anthropomorphic representations of Naga at Mathura start as early as the 3rd

century B.C.E, culminating into the establishment of the two Apsidal Temples

dedicated to the cult at Sonkh. The lack of iconographic evidence in the Gupta,

and later in the medieval period, is interpreted as the result of the

absorption of the cult into the ever-growing Brahmanical pantheon. At the same

time, the evidence of the worship of Balrama, running parallel to the other

Naga deities at Mathura, is seen in the many kinship triads depicting the

Vrishni heroes, Balrama being one of them along with Vasudeva. Since in the

literary texts, Balarama is associated with Krishna, who is also identified as

Bhagavata Vasudeva, the epigraphic evidence from the doorjamb inscription from

Mora, dated to the 1st century B.C.E, a mention has been made of a shrine that

was dedicated to Bhagavata Vasudeva, but Joshi feels that the inscription could

be well read Bhagavta Baladeva as well. Therefore the crux of his theory is

that while the worship of local, or folk as he terms them, Naga divinities was

popular in Mathura from the 3rd century B.C.E continuing to the early Gupta

period, there is equal evidence for the worship of Balrama during this period

as well.

The early Naga imagery from Mathura went a long

way in defining and refining the iconography of the Balrama images of the

region, but a well-developed independent formula for Balrama was yet to come

into existence.

The followers of Krishna therefore, according to

common scholarly perception, declared the Naga images to represent the older

brother of their divine hero. The conversion was made in such a manner that the

rural population could still continue to worship their familiar snake hooded

idols under a different name. The imagery of Krishna subduing the Kaliya Naga

in some ways is used as a metaphor to represent the undermining of the popular

cult of the Nagas, and the superimposition of the greater Vaishnava worship

over them. The Buddhist sangha, it is assumed, absorbed the Nagas into their

religious imagery due the immense popularity of the latter cult with the common

population.

In a recent study, Julia Shaw and John Sutcliffe

have added the dimensions of economic determinism to this assimilative

practice. They feel that the traditional models on Buddhist propagation in

ancient India, address the issue of the Sangha's appropriation of the local

nature spirits, drawing from textual accounts the Buddha's subordination, and

the ultimate conversion of the powerful Nagas and Yakshas.

From the observations and chronicles of Faxian,

the Chinese pilgrim, who visited India in the 5th century C.E., the

incorporation of the Naga shrines into the monastic compounds was largely

connected to the popular perception of the Nagas as fertility and protective

deities, and that such a practice would therefore ensure adequate rainfall and

protection against natural calamities. Shaw and Sutcliffe have taken up the

case study of the Sanci landscape, and argued for a model of monastic

landlordism according to which they claim that the 'spatial dynamics of the

"early historic complex" are repeated throughout the Sanchi area and

it provides an empirical basis for suggesting some form of interdependent

exchange network between local oligarchs, landowners, labourers and monks.

How do the Naga images figure in here? First,

the presence of the Naga images situated within the boundaries of the hilltop monastic

complexes are seen to form a part of the wider 'Buddhist landscape', and

secondly, these images are seen as manifestations of the local Naga dynasty,

who appear to have been closely connected with the patronage of dams and

Buddhist sites in the area.

Further the association of the Nagas with water

and fertility in the common belief systems of the people also encouraged the

monks to have their images installed within the monastic complexes, or near the

water bodies like the dams in the area. Therefore Naga worship as part of

Buddhist practice was not because the Sangha sought to convert the local

population, but rather because its effects were in harmony with the Sangha's

wider economic concerns with agrarian production as an instrument of lay patronage.

There are two aspects to the argument made by

Shaw and Sutcliffe, one concerning the role of the monastic establishments in

agricultural expansion, and the second, the role the Naga deities played in

this practice of rural expansion/monastic landlordism that was undertaken by

the Sangha. While the first part of the argument is worked out well, using

archaeological data, with regard to the spatial distribution of monasteries in

the countryside of the Sanci landscape, the connection made with the Nagas is

not very clear especially, with respect to their role in this economic process

and their concomitant assimilation within the Buddhist sect. There have been

many arbitrary presumptions that are made in drawing out this working

hypothesis of the growth and development of the Naga cult in general, and its

assimilation into the larger religious systems of the ancient period.

First is the assumption that the Naga cult was a

folk or a rural form of worship, primarily associated with agriculture. This

has prevented any further studies on the specificities and the finer aspects of

the growth and development of this cult in specific regions, in my study this

is applicable to Mathura. Secondly is the claim, that these cults and their

modes of worship are absorbed into, and modified by the larger pan Indian

religious systems like Buddhism, Jainism and later the all-encompassing

Brahmanical pantheon. The example of Mathura is quoted by Shaw, while

discussing issues of assimilation and integration, stressing the fact that the

Nagas were gradually assimilated into the Bhagvata tradition, and thus the

iconographic resemblance of the ancient Naga and later Balrama images is no

coincidence. The fact that Balarama in the Bhagvata tradition is a deity

closely associated with agriculture, provided further credence to the theories

of fertility and the agrarian aspects of the Naga cult. Issues of royal

patronage are thrown into the argument by using the evidence of the political dynasty of the Naga rulers in the region, who were

believed to have greatly supported and patronized the cult. Therefore, though

issues of economic determinism and the theories of monastic landlordism may

seem plausible to an extent, the association with Nagas and the functional

aspect of the cult in this process remains precarious.

Confining our study to the region of Mathura, we

argue that the Naga cult in the region, during the period under study, enjoyed

unparalleled popularity and was equally complex and diversified as any other

major religious cult of the time-be it Buddhism, Jainism or the Vasudeva cult

at Mathura. Naga icons at Mathura do form a part of the Buddhist and Jaina

pantheons, but there is an overwhelming amount of sculptural representations of

Nag a divinities that are worshipped in their own right. It can be agreed upon

that perhaps the popularity of the Nagas at Mathura encouraged the Buddhists to

assimilate them into their religious iconography and represent them in the

Buddhist architecture at Mathura, but at no point of time in the region does

the Buddhist faith supersede the popularity, or is able to fully convert the

Naga deities into being a subsidiary part of their religion. On the contrary

the Naga cult at Mathura continues to run parallel to the Buddhist one, and

both coexisting in the same landscape enjoyed generous patronage from the local

population. There is no evidence of contestation or confrontation between the

two cults, but an amicable sharing of the same space, as well as a healthy

interaction between the two religions?

The assumption that the Naga cult received any

Copious patronage from the political dynasty of the Naga rulers at Mathura, and

that the Naga religion played any role of legitimation, which may be evident

from the Naga kings being portrayed as manifestations of the Naga divinities,

is not borne out by archaeological evidence. Going by the sculptural data

available, the Naga imagery at Mathura begins as early as the 1 st Century

B.C.E, way before the Naga dynasty is established at Mathura, even the Apsidal Temples at Sonkh dedicated to the cult predate

the Naga dynasty at Mathura. The epigraphic evidence also does not provide any

indication to extensive patronage by the Naga rulers. In fact almost all of the

inscriptions on the Naga images are dated to the Kushana period and mention the

names of the Kushana rulers, primarily Kanishka and Huvishka.

Theories of economic determinism or monastic

landlordism are not really applicable for the region of Mathura, which is

predominantly perceived in literary sources as a region closely connected to

the trade nexus of North India, and archaeological evidence has not revealed

any monumental architecture that may be connected to any extensive agricultural

practices in the region, for instances dams or reservoirs as in the case of

Sanci. Further throughout our work, We have argued, that Mathura as a region

was extremely cosmopolitan in nature, and the spatial dynamics here were very

complex, thus the region cannot be distinctly divided into urban and rural

pockets. The religious cults of Mathura formed a part of this larger

cosmopolitan set up and operated at different levels, the Nagas being no

exception. The ritual and functional importance of the Naga deities, in the

Buddhist pantheons in particular, and in the region of Mathura in general, is

therefore, different to what it may be in the case of Sanci or other Buddhist

sites.

It also seems evident that the Naga cult in

Mathura was extremely local or regional in nature-that is to say that some of

the Naga deities are mentioned by name in the inscriptions and these seem to be

popular local Naga gods worshipped by the people of Mathura. The sculptural

representations of the Naga divinities at Mathura is also extremely diversified

and include individual standing Naga figures, as well as Naga and Nagi plaques,

sometimes being adored by a group of worshippers. The Naga-Nagi plaque from the

site of Dhruv Tila represents the two figures standing side by side holding

water vessels in hand. A similar sculpture, dated to the Kushana period is

found from the site of Ral Bhadar in Mathura, where a Naga figure is t1anked on

each side by two female Nagis, on the pedestal is a group of twelve figurines,

five males, five females, and two children, probably representing the donor and

his family. The inscription on the pedestal is dated to the reign of Kanishka

and records the donation of a tank and a garden to the Naga lord, who is

mentioned by his name as 'Naga Bhumo'. In other two sculptures the female Nagi

is depicted alone flanked by two attendants holding spears in their hands, the

canopy over the head of the Nagi consists of a row of radiate heads.

From the headless Naga figure obtained from the

river Yamuna, the inscription engraved in Kushana Brahmi reads the name

'Dadhikarna', which probably was the name of the deity. As it has already been

discussed that the temple of this Nagaraja existed at the site of Jamalpur,

therefore this image would also have belonged to that site and would have

represented the said Naga deity. The Naga Bhumo is mentioned in the Ral Bhadar

plaque and in many other cases the Naga deities are simply referred to as the

'Holy One'.

The regional and local popularity and

significance of these deities is further emphasized by the find of a Naga-Nagi

plaque from an unknown site from Mathura, dated to the reign of the Kushana

king Kanishka, donating the a temple to the Naga goddess on behalf of the

entire village.

The Popular Regional Cults of Mathura

The history of ancient Indian religion is

primarily traced from the Sanskrit and Pali sources, signifying the development

Vedic religion in the ancient past, to the growth of sects like Buddhism and Jainism,

followed by the complex development of the Brahmanism, that later in the modern

period came to be referred as Hinduism. Mythology and legends as part of this

religious literature provide insights into the history of religious cults

prevalent in a region. These sources provide regional references to the

mythical characters and gods and goddesses, and to various events that take

place in a region. The stories or the life events of Krishna and his entourage

at Mathura are a good example of this. Similarly, the Buddhist sources mention

certain places that are associated with important events from the life of Buddha

that later are considered sacred to the followers of the religion. Though

religious cults like Buddhism, Jainism and branches of the Brahmanical religion

like Vaishnavism are considered pan-Indian in nature, the literary texts

provide certain regional, spatial and temporal contexts to the development of

these religious cults. Alternatively, these religions are then perceived to

constitute the popular cults of those regions. These literary references are

then corroborated with archaeological evidence from the specific regional sites

to provide incontrovertible proof for their existence and practice in the

region.

Archaeologically, the presence and popularity of

a particular religious cult in a region is usually gauged by the extent of

monumental architecture, sculpture and epigraphic evidence dedicated to that

particular cult. This is often taken in association with the textual sources

that will in some ways provide a cohesive framework within which this

archaeological data can fit in, and a linear trajectory to the growth and

development of that religious cult in a specific region be traced. A

distinction is further made between the mainstream religious cults and the

other 'folk', 'rural', 'tribal' or 'popular' cults that may have also coexisted

within a shared geographical space. The latter are always studied as being

subordinated or subservient to the larger religious systems, and are perceived

as often being erased out or assimilated within the mainstream religious cults.

The Nagas, Yakshas and other local gods and

goddesses form the category of the so-called rural or folk cults at Mathura.

These is largely due to the fact that these cults do not have any extensive

religious literature attributed to them, nor are there any large-scale

religious buildings dedicated to them. But this may not always be the case, for

instance the scale and organisation of the Naga cult at Mathura need not be

re-emphasised. Out of all the sites that have yielded Naga images at Mathura,

Sonkh seems to have been the stronghold of the cult in the region. Further in

almost all the inscriptions, mention is made of temple structures being

dedicated to the Naga deities. The Naga Bhumo from the site of Ral Bhadar is

dedicated a tank and a garden, the Chhargaon Naga image, according to the

inscription on it was set up at a tank dedicated to the Naga, and the temple

ofthe Naga Dadhikarna at Jamalpur is well known from the inscription.

Similarly, in the case of the Yaksha cult at

Mathura, there are no elaborate religious texts that trace the origin and

mythology of these cults, neither are there, any huge monumental architectural

structures that are dedicated to them. The references to the Nagas and Yakshas

in textual traditions are very ambivalent in nature, this being particularly true

for the Yakshas, who are viewed as both malevolent and benevolent deities.

Coomaraswamy while tracing textual references to Yakshas in the Vedic sources

begins with discussing the etymology of the word 'Yaksha', and believes that in

the earlier texts the word has been described variously and its meanings have

been much disputed amongst scholars. Therefore in strictly Vedic terms it may

be translated as 'sacrificial offerings' or at times it is used for 'worshipful

deity' or even a 'phantom'.

The haunt or abode of a Yaksha can be outside a

city, in a grove or a park, on a mountain or a ghat, by a tank, or at the gate

of a city or even within the palace precincts. The Yakshas in most cases,

especially in the Pali Buddhist sources have a very regional context and are

seen as being associated with specific cities or inhabiting the forests or

outskirts of a urban centre. These Yakshas were at times also seen as

malevolent creatures that are to be propitiated with offerings and were finally

subdued by Buddha, who then converts them into benevolent deities. The Nagas on

the other hand, are mentioned in the Epics to have inhabited an abode of their

own, which was the underworld or the patalaloka. They appear as constituting

the group of the demigods in Buddhist literature to which belong the Devas and

the Yakshas as well. Both the Nagas and the Yakshas were worshipped under

similar conditions in the Early Historical Period, and both were depicted by

the main religious movements as adherents to their doctrines, and later getting

integrated into their respective pantheons. The Nagas and Yakshas therefore, in

literature are always placed in a subservient position and are eventually

portrayed to be assimilated into the mainstream religious systems.

However the popularity of the cult of the

Yakshas and Nagas in the region of Mathura is unchallenged. Most of these gods

and goddesses operate at a very local/regional level, and are worshipped in

different ways by the local population in Mathura. The earliest literary acknowledgement

of these regional deities is perhaps in the Arthasastra of Kautilya that takes

into account the presence of desadevatas or desadaivatas, which refer to the

tutelary deity of a region or a kingdom. Kautilya also acknowledges the

existence of local rituals and means of worship at the local temples and the

fact that people stuck to their beliefs and practices that they were accustomed

to.

One can also observe the different levels at

which these cults are operating. While the Naga cult at Mathura had temple

structures and tanks built and dedicated to them, as the Buddhists and Jains

had monasteries and temples, a lot of local cults flourishing in the villages

and cities in Mathura did not have any monumental architecture associated with

them. The cult of the Yakshas and village gods and goddesses were some of them,

yet they had a large following amongst the people and were as popular as these

other mentioned cults. In most cases the Yaksha images were placed in an open

space probably under a tree and worshipped, and hence did not

have any architectural monuments dedicated to them. The freestanding image of

the ancient Manibhadra Yaksha from Parkham is an example of a cult, which

seemed to have been very popular. The Yaksha is worshipped till date in the village

and an annual fair is held in its respect in the month of Magh (January). The

same can be true of the various local village gods and goddesses, as well as

common ancestors that are worshipped throughout the region today. We do not

find any big temple structures associated with them, but there are local

shrines at sacred spots consecrating a male and female deity respectively.

These may have, in the ancient period, taken forms of stone slabs or sacred

altars placed under trees and could be worshipped by local people who

worshipped them with offerings in their own ways.

Coomaraswamy points out to this fact that a lot

of tree spirits and local deities were worshipped in this manner, and that the

sacred tree and the alter are two elements of local practice that may have been

taken over by Buddhism by older cults, and in the case of the Bodhi tree this

transference can actually be seen. It is believed by scholars that even the

Jaina tradition of the ayagapattas may have emerged from these sacred altars and

slabs placed on small platforms for folk divinities? This could be an example of certain popular

religious practices being assimilated and modified and then incorporated into

the Jaina religious system. But assimilation could work the other way round as

well. Vidula Jayaswal in her ethnographic study of the use of terracottas in

the Ganga Valley sites highlights the existence of many Devi-thanas and

Baba-thanas, which are local shrines consecrating male and female deities

respectively. She feels that though the local goddess here is seen in relation

to the Sakti cult, yet the custom originated essentially on the local

magico-religious practices? Even in the

present times, though these small structures are said to represent Durga or the

Sakti cult, the modes of worship and offerings to these are defined by the

popular belief systems and local practices. There are no elaborate Brahmanical

rituals that are carried out at these shrines.

The diversity of the local cults in Mathura

during the ancient period was perhaps also reflected in the sculptural data.

The various categories of the Yaksha images would have represented these

innumerable divinities that were worshiped throughout the district. Though

scholars have identified and discussed some of these deities, like Moggarapani

Yaksha, Kubera, Hariti or Naigamesha images, there are many others that do not

lend themselves to any identification because they are not mentioned in any of

the religious literary texts. Apart from the stone sculptures, Mathura has also

yielded a variety of terracotta images of probable female Yakshi. All of these

local goddesses could have formed an important part of the local belief system

of the region, and could have had popular local legends associated with them,

that do not get reflected or recorded in the religious literature of the

period. The regional context and the local popularity of these cults are also

reflected in the fact that most of these images were consecrated in smaller

makeshift shrines, located at a sacred spot in the villages and the deities

were too well known to the people to have their names categorically spelt out

in the inscriptions.

The legends and the stories of these local gods

were perhaps circulated amongst the local population in form of popular stories

and became part of larger oral traditions that never found mention in any of

the literary writings.

The pilgrim circuit of

Mathura today is dominated by the Krishna bhakti and most of the sacred spots

are associated with the Krishna legends. However within this tradition are

vestiges of the ancient cults, like those of the Nagas, Yakshas, local devis

and devatas. The fact that a good number of devi shrines remain integrated with

the brajparikrama shows the resilience of these cults. The presence of the worship

of various sacred trees and groves in the Krishna bhakti can also be seen as

the continuation of older practices of the worship of tree spirits that played

an important part during the ancient period at Mathura. In the present times at

Mathura when even the ancient images are salvaged by people to be worshipped as

some Brahmanical deity, as is done with the ancient Naga image at Sonkh, which

now enshrined in a temple and plays the part of goddess Camunda, there are a

number of local spots with small shrines and icons that form a part of local

religious practices connected to ancestor worship of some tutelary deities. The

Parkham yaksha is a perfect example of the resilience of these

popular cults.