The subject of our research is a people that

official historians refer to by many names. These names are the following:

Sweta Hunas or Khidaritas in Sanskrit, Ephtalites or Hephtalites in Greek and

in the European languages, Haitals in Armenian and Heaitels in Arabic and

Persian. The Byzantine historian, Theophylactos Simocattes, called them

Abdeles, while, according to the Chinese Annals, the name of this people is

Ye-ta-li-to because their ruler was called Yertha (Hephtal). The earlier Indian

sources called them the Chionites. However, all these different names refer to

only one people: the White Huns. In the historical texts they are indicated as

Hephtalites.

For a long time, it was debated whether they

were identical to the Hsiung-nus, who originated from China, split up many

times and finally settled in the Oxus (Amu-Darya) Valley, At that time, they

were already called Western Hunas in Indian sources. From the northern

Hsiung-nus originated the Asian Huns - or the Black Huns - who moved first to

the Caucasus, later on to Europe and became a world power. They were the people

of Balamber - Munduk - Rua - Atilla - or the ancestors of the Hungarians.

The many archeological finds, excavated since

the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries, the Sanskrit

literary and religious works from the early centuries C.E. and, last but not

least, the accurate Chinese Annals, chronologically parallel to the Indian

sources, prove that the greater part of the White Huns consisted of the Western

Hunas. The famous Chinese Buddhist monks — one of them, Sung Yun, who visited

India at the time of the Hephtalite kingdom - and the other, Hsuan Tsang, who

went there a few decades later, gave details about the White Huns in their

accounts. However, the Hephtalites had mixed with other nations before they

arrived in India,

The early appearance of the hephtalites

The Western Hunas appeared in Transoxiana - the

grassland between the Rivers Oxus (Amu-Darya) and Jaxartes (Sir-Darya) - at the

end of the 3rd century C.E. At that time they did not mix with other tribes

but, because they had a strong army and they were remarkably brave, they

conquered more and more territories south of their settlements. At the

beginning of the 4th century C.E, they occupied Tokharistan and Bactria (now

North Afghanistan), The Greek historian Proeopius distinguished them from

Atilla's Huns, who wandered toward the west and conquered a great part of

Europe. According to him, their culture and appearance were better than those

of the Northern Huns. Proeopius wrote that the Hephtalites were taller, more

beautiful and their skin was fairer than that of the Asian Huns. Here we should

mention that the colors written in the ancient sources did not indicate the

skin color. The Northern Huns were the Black Huns because, in their ancient

history, they had adopted the names of colors in agreement with the four

cardinal points. It was customary among the Central Asian peoples. "Black"

always indicates the more severe, northern region, "white" means the

western, "green" or "blue" means the southern, while "red"

indicates the eastern territories, so the descriptions of color are not

connected with the people's skin color. The majority of researchers state that

the Chionites or, as they are also known, the Hionos joined the White Huns

already in Transoxiana. They were related to the Western Hunas. Other scholars

theorize that the White Huns were the descendants of the Kushans - or as they

are known in Persian: the "shanan-shahis" (the Kings of the kings)

living in Bactria and Gandhara (now North Pakistan) at that time. The Kushans

were defeated by the Sassanians in 239 C.E and became their vassals, yet they

had relative independence. The Hephtalites confirmed the later opinion, too,

when, mainly in the first period of their conquest, they called themselves

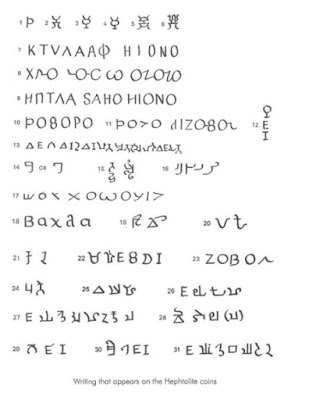

"shahan-shahis" on their coins. They used the Greek script and the

Bactrian dialect of the Persian language. They wanted to prove, by their coins,

that they were the successors of the Kushans and that they could rightfully

claim the occupied territories.

As a matter of fact, the above-mentioned

scholars are correct. The main body of the White Huns consisted of the Western

Hunas, who had separated from the Hsiung-nus. However, the Chionites and the

Kushans of Bactria joined the newcomers, the strong people of Central Asia.

They hoped that, with the help of the Hephtalites, they could re-conquer their

East-Iranian and north-north-western Indian territories. The Khidarites - who

also joined the White Huns — belonged to the later Kushans, too. A Ta Yueh-chi

(Great Yueh-chi) prince, Khidara, and his tribe became independent from the

Sassanian rule at the beginning of the 4th century C.E and occupied the eastern

part of Gandhara, This fact is proven by the Khidarita coins excavated there.

The pillar found in Allahabad, India proves this, too, as the following text is

written on it: "Near the border of Northern India lives a prince called

Devaputra Sahanushahi (son of God - King of kings)". As this title always

belonged to the Kushan rulers originating from the Great Yiieh-chis, it means

that Khidara was their successor and the Khidarites were his nation. According

to archeologists, the pillar was constructed around 340 C.E, so the

Hephtalites and their "kindred tribes": the Kushans, the Chionites

and the Khidarites, arrived at the Indian border at that time.

The Hephtalites in Persia

After occupying Bactria, the strong White Hun

army made its way toward Persia. The fact that a so-called nomadic nation, like

the Hephtalites and their predecessors, the Kushans, wanted to conquer the

settled, wealthy peoples of ancient culture was understandable from their point

of view. The nomadic nations were stock-breeders and agricultural peoples in

the Bronze Age, according to the archeological finds. However, because of the

climatic change in Central Asia, their cultivated fields became steppes or even

uncultivable deserts. At that time, they adopted the nomadic, pastoral way of

life "with their high degree of adaptation to the environmental

possibilities". These harsh circumstances made them strong, brave

warriors. Since they possessed only the products derived from stock-breeding,

and the exchange of these products did not cover their needs, sometime they had

to plunder the richer settled countries surrounding Central Asia. For them, war

was almost a profession of livelihood. Initially, they obtained their booty or

tribute from China but the Chinese began to build walls as a protection against

them.

After that, the nomads wandered toward the west;

one group of them occupied the Transcaucasian territories, while others

migrated to the south into the small oasis-states of Fergana and Sogdiana and

later to Bactria and Gandhara; finally the "fabulous India" became

the target of their conquests. They were slowly assimilated into the peoples of

the occupied lands; the majority of the tribes even settled there because they

did not want to go back to the severe climate of the steppes or the deserts.

It is clear from the archeological finds of the

Kushans and the Hephtalites that their kings tolerated nearly all the Asian

religions and adopted the customs, languages and religions of the occupied

countries. We can find the symbols of the Zoroastrian, Buddhist and Shaiva

religions on their coins; moreover the Greek deities appear on the Bactrian

finds, characteristic of the late Greco-Bactrian period. We can see the script

and language of the conquered countries. On one side of the coin the king's

name and title are written in Greek letters in the Bactrian dialect of the

Persian language, while on the reverse with Kharosthi script, in Prakrit or

with Brahmi script, in Sanskrit. These facts prove their high degree of

adaptability.

The wars fought against the Sassanians in Persia

actually started because of the Sassanian king, Firoz. He withheld the war

booty, or at least a part of it, from the Huns, although it was necessary for

their living. The Hephtalites came into contact with Yazdigird, the Sassanian

king, in 457 C.E, winning many successful battles against him. After

Yazdigird's death, his son, Firoz, was the heir to the crown but his younger

brother, Hormuzd, deposed him. At that time, Firoz asked the Hephtalites for

help and, together with them, he defeated Hormuzd and his army. The King of the

White Huns was called Khushnewaz and he already ruled Tokharistan, Badakshan

and Bactria. Firoz - though the chiefs of his army warned him - did not pay the

agreed war tribute and even started a war against the Hephtalites. He lost the

war and a part of his army was destroyed. The White Huns occupied the important

town of Gorgo at the Persian-Bactrian border. Firoz again attacked the

Hephtalites, taking his sons with him; he left behind only his youngest son,

Kubad. The Sassanians suffered a crushing defeat; Firoz and his sons died in

the battle. The Sassanian Empire became the vassal of the Hephtalites for a

short time. They paid a war tribute every year and they lost two important

provinces: Merv and Herat. After the Persian victory, the White Huns prepared

for a new conquest: India.

However, before writing about the wars in India,

we should refer to the sources mentioning the White Huns. Besides the

well-known European and West Asian sources: e.g. Proeopius, Theophylactos

Simocattes, Moses Khoreni, Jordanes, Ammianus Marcellinus and Cosmas

Indicopleustes, primarily the always correct Chinese Annals and the reports of

two Buddhist monks, Sung Yun and Hsuan-tsang, the Arabian Al-Beruni and the

Persian Fir-dause help us to understand that era. However, because a

significant part of the Hephtalite kingdom belonged to ancient India, the

Indian literary works, religious scripts and archeological finds contributed to

the revelation of their history. The research of the White Huns in Hungary was

insufficient because it did not take into consideration the Indian sources.

The Hephtalites, while still living in the Oxus

Valley in the 4th century, are mentioned in the Indian Puranas, written in

Sanskrit. First of all, the Vishnu Purana and the Aitar-eya Brahmana refer to

them, calling them "Hunas". At the beginning of the 5th century, the

famous poet-writer, Kalidasa, writes about them in his Sanskrit epic: the

Raghuvamsha (Raghu's nation):

"Tatra Hunavarodhanam bhartrishu

vyaktavikman Kapolapataladeshi babhuva Raghuceshtitam"

The abovementioned quotation translated:

"The Huns live in the Oxus Valley. They were created to practice power but

the cheeks of their wives blush when they hear of the victory of the heroic

Raghu." The other important literary work is Kalhana's Rajatarangini (The

Chronicle of the Kings). This work of many volumes by the Kashmirian historian

was first translated from Sanskrit into English by Aurel Stein in 1900 C.E.

The data in Kalhana's work should always be

compared with other sources because the Kashmirian author dealt freely with the

historical facts and dates. However, the names of his books are real and, if we

compare his dates with the correct Chinese sources, and the Sanskrit and

Prakrit epigraphs and coins found at the archeological excavations, we can

obtain the exact data.

Apart from the above-mentioned sources, there is

the poem: Harshacarita (The deeds of Harsha) written by Bana, the court poet of

King Harsha (606-640 C.E), In this poem, Bana mentioned that the father of the

famous Indian King Harsha finally defeated the Huns at the beginning of the 7th

century. We should mention that this was not true because, according to the

Puranas, the Huns ruled India for 300 years, though after 565 C.E only in

Kashmir and in a part of Punjab, but still it was a large territory.

The other important and frequently quoted work

is a Jaina religious book from Jaisalmer, Rajasthan. It is the Kuvalayamala.

Moreover, the epigraphs found on pillars, temple ruins and buildings of that

period can help us to identify the names of the rulers, the date of their

reign, their wars, and victories or defeats. We shall refer to the sources in

the proper places in this essay.

The Hephtalites in India

The noted Indian scholar, Professor Modi,

remarked: "The Huns always headed for India, whether they were victorious

or defeated; in the first case they felt their power and in the second case

they wanted new grazing grounds and booty."

Modi's statement is supported by the Indian

sources; according to them, the first Hun attack against India took place in

455 C.E in the Punjab - now in the territory of Pakistan - but, at that time,

the Indian King, Skandagupta, defeated them. This fact was recorded on the

pillar of victory set up in Bhitari:

"Skanda Gupta of great glory, who ruled by

his own power, the abode of kingly qualities, after his father had attained the

position of being a friend of the gods (that means, he had died.E. A.) - and

whose fame was recognized even among his enemies in the counties of the

Mlecchas (slaves, strangers E.A.) ..... after he had broken their pride down to

the root, announced: verily the victory had been achieved by him."

The word, Mlecchas, or strangers of lower caste,

naturally meant the attacking Huns. So, at that time, the Indian army was

victorious. The same epigraph was written on a stone pillar in Western India,

in Junagadh. Junagadh is situated in Gujarat Province near Kathiawar; this

place was Skandagupta's headquarters and he wanted to announce his victory

there, too. The above-mentioned Bhitari is in Punjab.

The latest researches and the excavations in the

north-western part of Pakistan - where some Hephtalite coins and epigraphs were

found - prove that Toramana (his original Hun name: Turman) was not the first

major Hun ruler in India. On the coins, the names, Tun-jina or Tujina, are

written in Brahmi script and, on the reverse of the coins, his titles, tigin or

tegin, are given, too. It seems that the dual power was well-known by the White

Huns, as Tunjina was war lord and ruler, while the seat of the kagan was near

Bokhara in the north; this fact we know from the Persian sources. The title

"tegin" already existed at the time of the White Huns, as is proven

by their coins. It is not true that this title appeared only later with the

Khazars and the Avars.

Moreover, the name Tunjina was mentioned in

Kalhana's Rajatarangini as the first Hun ruler who entered India and invaded

Kashmir. As we mentioned before, Kalhana's work should be treated cautiously

because he wrote it in the 12th century C.E and, although he referred to

authentic historians, it is primarily based on traditions and legends. The

names of the historical persons and the stories belonging to them are real, but

the chronology is uncertain. His data should be compared with other sources.

Therefore, from these other sources, the fact is proven that the father of

Toramana, and the founder of the conquering dynasty, was Tunjina. He was ruling

from 465 to 484 C.E, so the first Hun campaign in 455 C.E was not commanded by

him. This battle ended with a Hun defeat. However, in 475 C.E, Tunjina quickly

and successfully entered India with his army and occupied the Punjab and even

the northern part of the Ganges Basin. In 484 C.E, his son, Toramana, the

energetic and talented tegin - war lord - became the leader of the Hephtalites.

Toramana

First of all, we should mention the Indian

epigraphs that prove Toramanas reign and his conquests. We know of three such

stone inscriptions:

1) The Eran statue inscription. Eran was in the

northern part of the province of Madhya Pradesh, so almost in the center of

India. It seems that the Hephtalite ruler had already conquered Northern and

Western India. The statue most probably stood in front of a temple built for

Vishnu and the following text is written in Brahmi script on its pedestal:

"In the first year of the rule of

Maharajadhiraja (the King of kings): Shri Toramana, who is governing the earth

with great fame and luster."

2) The inscription on the Kura main pillar. Kura

is a town situated in Northern Punjab - today it belongs to Pakistan. The

following text is written on the stone pillar in Brahmi script:

"This was engraved during the reign of Maharajadhiraja

Shri Toramana, the great Saha Javlah."

There is no date on the inscription but we are

sure that it was made in the last quarter of the 5th century. The title:

"King of kings" - in Sanskrit: Maharajadhiraja - is engraved in both

the stone epigraphs but, on the Kura pillar, the title, Saha, can be seen, too.

This indicated that he and the Hephtalites were the rightful descendants of the

Kushans, since the Kushan kings had used this name, though Toramana kept his

own Hun identity to some extent, as the word "Javla" appears on the

pillar inscription. Researchers offer different interpretations of this word.

On the one hand, it means the birthplace of Toramana, the city that had been

their head-quarters since the Persian and Gandharian wars, namely Kabul. They

called this city in their own language: Jaula, Javlah, Zabula or Zabola. These

names can be found on their different coins. So the title Saha Javlah means:

"the ruler from Kabul". However, the words: "Javlah, Juvl"

meant "falcon" in the old Turkic language; this could have been the

sacred bird of the White Huns, as the turul falcon is that of the Hungarians.

Therefore, if the words Javlah, Zabula, Zabola meant the name of the city, we

should mention that these words are also of Turkic origin. In the eastern part

of Iran, near the Afghan border, there is a town called Zabola, and in

Transylvania, too, we know of a place called Zabola.

3) The Gwalior inscription. Toramana is

mentioned on this, too, but the inscription was made during the reign of his

son and successor, Mihirakula, most probably in 530 C.E It was engraved on a

pillar of the temple, built for the worship of the Sun God and Shiva. Gwalior

is a town in the center of India.

After mentioning the usual laudatory titles, the

epigraph informs us about the exact date of the temple's erection, which was

the 15th year of Mihirakula's reign. This means that Mihirakula ruled from 515 C.E

and his father, Toramana, between 484 and 515 C.E. The text of the inscription

follows:

"Of him, the fame of whose family has risen

high, the son of Toramana, the Lord of the Earth, who is renowned under the

name Mihirakula, who unbrokenly worships Pasupati."

Pasupati is one of Shiva's different names. It

appears from the epigraph that both Mihirakula and Toramana were followers of

Shiva.

Besides these three inscriptions, numerous coins

give information about the first really important Hun ruler, who - according to

the sites where these coins were found - occupied Bactria, Eastern Iran,

Gandhara, Kashmir, Northern and North-Western India, as far as the Ganges Plain

and Rajasthan in the west and Madhya Pradesh (Middle Province) in the center of

India. This means that he ruled almost half of India. During his long reign, he

won many successful conquering wars. The Toramana coins were current even in

the 18th century in the Kashmirian bazaars. On his coins appear the names

"Sahi Zabula" or "Sahi Jauvla" and, on the reverse side,

Shiva and his animal carrier, the Nandi bull, or the symbol of the Sun God, the

Sun-wheel is visible. Obviously the worship of the Sun God was their original

nature-religion. However, as one of the best Indian Hun researchers, Atrevi

Biswas, noted in her book "It is a remarkable feature of the Central Asian

invaders that, wherever they went, they adopted the local customs, beliefs and

traditions, even the languages, and they adapted themselves according to their

new environments. This strong quality of assimilation persisted when they

entered India,"

Besides the stone inscriptions and coins, the

Buddhist religious books - the already-mentioned Jaina Kuvalayamala and

Kalhana's Rajatarangini - inform us about the White Hun king. From these

sources - though not always authentically — we may get some data about

Toramana, the war lord and the man. He occupied almost half of India's

territory in the first year of his reign, in 484 C.E, as the Gupta Empire had

become weak by that time, and the smaller Indian principalities were fighting

against each other. We can conclude, on the basis of the above-mentioned works,

that "Toramana was a remarkable and talented personality, whose

achievements in India were no less great than those of Alexander. He was the

first foreign ruler in India, who built up a vast empire from Central Asia to

Central India. He was a born fighter who, with his well-organized army, gave

the Hunas a stable home for more than a hundred years, a better one than their

original home in Inner Mongolia. After Atilla, he was the only general who

re-organized the Hunas, under his inspiring leadership, to a nation-reborn

after many failures". He was not only a great conqueror but also a good

organizer and administrator. Indeed, he developed his own state organization:

Kabul and Purushapura (near Peshawar, today in Pakistan) became his

headquarters in the North and the territory of Malwa and its towns were his

center in the South. Malwa had also been the central place of the

Indo-Scythians and the Kushans. Malwa included the states of today's Rajasthan

and western Madhya Pradesh. Toramana appointed Indian princes to important

posts, ensuring their loyalty. He tolerated the three religions: Buddhism,

Hinduism and Jainism and even supported them. He did not change the

administration; he did not trouble anybody needlessly; there was a measure of

peace in the country; therefore the people accepted him.

After a long reign, Toramana died in Benares in

515 C.E Before his death, he declared his son, Mihirakula, his successor.

Unfortunately, the Crown Prince did not inherit his father's patience and

straightforwardness.

Mihirakula

He was a great conqueror but a short-tempered

man with a contradictory character; he ruled from 515 to 533 in the greater

part of India, according to the sources, and after two fateful battles, he

ruled only in Kashmir for some time. His name appears in the epigraph found in

Uruzgan, Afghanistan, as Mihiragula, It must have been his original Hun name;

its second part: gula indicates the name and royal profession of the Magyar

gyula, as he was a tegin and had the same duty as that of the later

"gyulas": a ruling war lord.

The inscriptions about Mihirakula are the

following:

1) The Gwalior inscription made in 530 C.E. We have mentioned it before, in connection

with Toramana.

2) The Mandasor inscription. Its date is most

probably 533 C.E It appeared only three years after the above-mentioned

epigraph and it informs us - in contrast to the announcement of Mihirakula's

victory in Gwalior - about his defeat by Yasodharman, a tribal prince.

The text follows:

"To the glory of Yasodharman, who occupied

the Earth from the River Lauhitya (Brahmaputra) up to the western ocean and

from the Himalayas up to the Mount of Mahendra, who forced the famous Huna

king, Mihirakula, to bend down his forehead by the strength of Yasodharman's

arm. Mihirakula's head had never previously been brought into humility in

obedience to any other, save the God Sthanu."

Sthanu is Shiva's other name; it is also proven

from the above-mentioned text that Mihirakula was a great devotee of Lord

Shiva.

However, the inscription glorifying Yasodharman

exaggerates - as was the custom of that time - because, according to the Indian

scholars, he was only a tribal prince in a part of today's Gujarat and, most

probably, he could not have ruled the great territory of India, up to the river

Brahmaputra. In the eastern part of the country the already re-established

Gupta Empire existed.

As we have mentioned before, the Mihirakula coins

were found first of all in Bactria, the territory of the present Afghanistan, and

also in Kashmir and in different parts of India. On one of the coins found in

Uruzgan, the next inscription appears, most probably in their own language:

"Boggo saho zovolovo Mihroziki", in

translation: "To the glorious King, Mihirakula of Zabul".

On one side of his silver coins, the King's

half-length portrait can be seen, with an inscription in the Persian language

and, on the reverse, appear the Sun-disk and the Moon crescent; sometimes the

fire-altar symbolizing the Mazda religion appears; on another occasion the bow

and arrow or the trident, the symbol of Shiva, appear.

The literary sources about the Hephtalites are

the above mentioned Rajatarangini and Kuvalayamala and the recollections of the

famous Chinese monk, Huan-Tsang, who went to India two generations later. His

accounts are based on legends and are to some extent exaggerated. Mihirakula's

contemporary, the Chinese pilgrim, Sung Yun, gives some information about the

Hun King and, although he does not draw a positive picture of him, his accounts

are free of prejudice. Sung Yun arrived in Kashmir in about 520 C.E. and

brought a letter from his master, the Chinese Emperor, to the Hephtalite King.

Aurel Stein's account about the story in the court of Kashmir follows:

"The pious pilgrim mentions that it was a sign of the King's barbarous

arrogance and self-conceit that he was seated while he listened to the Chinese

Emperor's letter of recommendation, while the other princes received the

message of the Son of Heaven, the great Emperor Vui, with full honors,

standing." The Chinese author added to his account: "Kashmir remains

under the power of a barbarous people."

We have to admit that the Rajatarangini is more

just to Mihirakula in this case, because according to Kalhana, the King

answered the offended pilgrim: "If the Emperor had come here personally, I

would naturally have received him standing but why should I pay respect to a

piece of paper?" This answer shows Mihirakula's sense of humor, too, but

there is no doubt that he was an arrogant and cruel ruler, according to all

sources.

However, he was an excellent military leader. He

inherited from his father a vast country and he extended it with his campaigns

to the South, as far as Indore - which is in the center of India, but the whole

subcontinent, even the southern provinces, became his vassal. A Greek

sailor-missionary, called Cosmas Indicopleustes, who traveled to India in 530 C.E,

gave an account about this fact in his book: Christiana Topographia. He wrote

the following: "India is ruled by the White Huns under the leadership of

King Gollas, who goes to war with 2000 elephants and a large cavalry. The whole

country is under his command and he takes tributes from far regions."

According to Stein, the name, Gollas, contains the second part of Mihirakula's

name (in the case of Greek authors, we should leave out the word-ending,

"s") and in this way we can get the word: gula.

According to the Rajatarangini, Mihirakula

persecuted the Buddhist monks but he was a follower of Hinduism, primarily the

Shaiva branch of it. He was a brave, strong warrior but fanatically held onto

his power. However, he built a temple called Mihireshwar, in Kashmir, near

Shrinagar, for the worship of Shiva and the Sun God.

Otherwise he was a simple person; he lived in a

tent among his soldiers and he was constantly fighting to keep the occupied

huge territories.

According to the Mandasor inscription, as we

mentioned before, Mihirakula was defeated in 533 C.E. by Yasodharman, a tribal

prince from Western India. At that time, he wanted to ensure his power in the

eastern part of his empire, but there, in the surroundings of Pataliputra (the

present Patna, capital of Bihar state) he and his army suffered a crushing

defeat from Baladitya, the king of the eastern province. Baladitya, the vassal

of Mihirakula, did not want to pay the tribute to the Huns any longer. The Hun

Emperor became very angry and started out with his army to punish the eastern

king. However, in the marshlands near the Bay of Bengal, Mihirakula lost many

soldiers, while his enemy and his troops knew their native terrain well. Baladitya, a devout Buddhist, did not kill his

enemy. The Hun Emperor withdrew to Kashmir, after the defeat, because he had

learned that his younger brother had occupied Shakala, his northern capital.

The Prince of Kashmir gave him asylum but Mihirakula overthrew the Prince with

intrigues and took the throne. He could not enjoy his power for long, as he

died of disease in 533 C.E. One of his successors was defeated in 558 C.E, by

the Sassanian King, Kushrew Anushirwan and, at the same time, by the Turkish

army in the North. The headquarters of the kagan - near Bokhara - surrendered

in 565 C.E.

The opinions of the Indian scholars are divided

about Mihirakula, the great conqueror, but the enemy of Buddhism, U. Thakur,

writes the following about him: "While his father gave a new country to

the Hunas and was accepted by the Indians, Mihirakula made the Huna name

dreaded and hated in India, The result was that, after a hundred years in

power, the great Hephtalite Empire ended and a talented people had to flee from

India." At the same time, another Hun researcher, Atreyi Biswas, pointed

out that the Buddhist accounts are always one-sided and exaggerated and the

actions of Mihirakula were not as cruel as stated by the Rajatarangini and the

two Chinese monks.

The traditions and the often-mentioned

Rajatarangini inform us that the rule of the Hephtalites did not end with

Mihirakula's death, and just state that this rule did not extend over the whole

country, not even over the larger part of it. The most reliable books of Indian

historiography are the Puranas and, according to them, the Huns ruled 300 years

altogether, primarily in Kashmir and in the greater part of the Punjab and they

had eleven rulers, including Tunjina, Toramana and Mihirakula. As the book

Rajatarangini should always be compared with other sources, in this case, with

the excavated coins and inscriptions, we may state the following with almost

full certainty: after Mihirakula's death, his youngest brother (half-brother),

Pravarasena, followed by his son, Gokarna: Gokarna's son, Khinkhila and his

son, Yudhishthira; and finally Khinkhila's grandson, Lakhana, ruled the

northern part of India until 670 C.E. - for 200 years, instead of 300 years

mentioned in the Puranas - since they won their first victory in 475 C.E.

However, the information in the Puranas was validated by the archeological

finds that indicated that isolated "Huna Mandalas" - Hun centers -

existed even in the 10th century, both in Rajasthan and in the North. The

account of Hsuan-Tsang also confirms the above-mentioned statements of the

Puranas.

When he traveled toward Nalanda in 633 C.E,

Hsuan-Tsang wrote about Kashmir and its people: "Fierce and wild people

live in this land; they are uncivilized and their language is different from

the Indian languages; it sounds harsher. They are a borderland people with

barbarous customs." His account is biased as he added: "the people

are non-Buddhist".

Pravarasena

He was Toramana's youngest son, who was a young

child when his father died in 515 C.E. We should mention that polygamy was

customary among the rulers both in Central Asia and ancient India. For

instance, in the Hsiung-nu history, we remember the case of Mao-tun sbanyu, who

was the Crown Prince but his father wanted to have him killed because he wished

to put his younger son on the throne. Maotun took revenge, when he killed his

father and stepbrother. But Rama, the hero of Ramayana, also had to go into exile,

because his father had promised his younger wife that her son would be the

crown-prince. In the case of Pravarasena, the situation was different. His

half-brother, the powerful Mihirakula, would not let him near the throne.

According to the Rajatarangini, after Toramana's death, Pravarasena was hidden

by his mother and uncle in a potter's house, then later he went to a northern

country and lived there as a pilgrim. We should mention that Pravarasena's name

is entirely Indian, unlike the names of his father and grandfather. Pravarasena

went back to Kashmir from the North, after Mihirakula's death, and ascended the

Kashmirian throne. According to the Rajatarangini this happened in 533 C.E but

some Indian scholars dispute this date because, after Mihirakula's death, a

prince from another dynasty ruled the country for some years. It seems that

Pravarasena's rule began in 537 C.E He was about 25 years old at that time.

According to Kalhana, he reigned for 60 years;

that means till 597 C.E. This is verified by the inscriptions and the books of

praise of the court poets of the Indian kings having connections with

Pravarasena - either as his allies or as his enemies.

With his army, he helped Siladitya, the Prince

of Malwa in Saurashtra (in the present Gujarat) to save the latter's throne

from Prabhakaravardhana, the King of Thanesar.

This means that he was a powerful and

influential ruler. According to the Indian researchers, Pravarasena later lost

an important battle to Prabhakaravardhana in the western part of India, This

fact was mentioned by Bana, the court poet of King Harsha from Thanesar. Bana

writes the following in his book praising the King: "Harshacarita"

(The deeds of Harsha):

"Vardhana was a lion to the Huna deer, the

axe, cutting the creeping-plant of Malwa's glory."

The battle took place in 587 C.E, and Vardhana

was Harsha's father. Malwa - the present Rajasthan - was always the center of

the Huns. Before that, it was the center of the Kushans; it was the

headquarters of both nations. The term "Huna deer" is interesting

because the deer was most probably their sacred animal, the symbol of the

Hephtalites, - in addition to the falcon: "Juvl" - and it was also a

symbol of the Magyars. In the excavated Hun graves in Mongolia, the pictures of

deer are visible on the fairly intact carpets.

The above-mentioned battle did not change the

fact that, according to the Rajatarangini and to the accounts of Hsuan-Tsang

the country of Pravarasena included Kashmir, the north-western part of the

Punjab, the Swat-Basin, the southern part of Bactria and Gandhara. It was a

large territory. The places where their coins were found prove that the

headquarters of the late Hephtalites were the same as those of their ancestors,

that means: Bactria, Kabul and the valley of the River Kabul,

The Rajatarangini mentions that Pravarasena had

a major town, called Paravarase-napura, built near the present Shrinagar, the

capital of Kashmir, Here, too, the Huns built a bridge.

Pravarasena had his own coins and on these - as

was usual on the coins of the Hephtalites - the word"Kidara" appeared

next to the ruler's name. They wanted to show their ancient Kushan-Kidarita

origin or relationship and the fact that they ruled the occupied territories

rightfully.

According to Kalhana, Pravarasena, although he

was the half-brother of Mihirakula, was a kind and wise ruler - contrary to his

predecessor - and he was accepted by his subjects during his long reign.

Among the Hun rulers in Kashmir, mentioned in

the Puranas, Pravarasena was followed by his son: Gokarna, who ruled for a

short time. Some of his coins were found in Northern India. His son, Khinkhila,

dedicated a temple to Shiva in Kashmir and ruled for 36 years, according to the

Rajatarangini. This statement was proven by the excavations undertaken in

Afghanistan in the second half of the last century, when archeologists found a

statue of Ganesha in Gardez, in the Swat-Basin, south of Kabul. On the base of

the statue, a few lines were engraved in Northern-Indian Brahmin script, most

probably in the middle of the 7th century. The inscription was engraved

for "Maharajadiraja Sahi Khingala", who was identified with the

above-mentioned Khinkhila by the scholars. So this means, the Rajatarangini was

right, only the date was incorrect; Khinkhila ruled between 600 and 633 C.E,

presumably, and his reign in Kashmir coincided with the Indian journey of

Hsuan-Tsang who stopped in Kashmir and wrote that its ruler was not Buddhist

and was descended from a lower caste. This description, from Hsuan-Tsang's

point of view, fitted Khinkhila, who, as a foreigner, was not considered by the

Indians to be a person belonging to a higher caste and, indeed, he was not a

Buddhist but a Shaiva.

When Hsuan-Tsang was returning home, after his

long Indian sojourn, he stopped again in Kashmir and, at that time, Khinkhila's

son, Judhishthira, was on the throne. The Chinese monk wrote highly about him.

According to the Rajatarangini, Judhishthira ruled for 24 years, from 633 to

557 C.E. Judhishthiras son, Lakhana. whose coins were also found, ruled for 13

years in Kashmir.

The names and dates of the reigns of the other

Hun kings - mentioned in the Puranas -are not provable. At that time, from 670 C.E,

another dynasty came to power in Kashmir.

The successors of the Hephtalites in India

After glancing over the data of the reigning

princes ruling in the northern part of India, let us see what happened to them

in the western and central parts of the subcontinent. As it was mentioned, some

Hun states were established in several parts of the territory of India, after

their defeat. They were the so-called Huna Mandalas - Hun centers - still

representing a considerable power. Previously Malwa was their main center,

including the present states of Rajasthan, East Gujarat and the western part of

Madhya Pradesh. Here, the Huns remained for a long time. This fact is known

from the "victory pillars", established by the Indian kings.

According to these, the Huns had to be defeated even in 900 C.E. This is proven

by the Garuda pillar from 850 C.E. It states that King Pala, who ruled in the

central part of India "defeated the Hunas, the Gurjars and the Dravidians

in the eastern and western parts of the country," where they also had some

centers, besides Malwa and Kashmir. This was the Uttarapatha Province, north of

Kanauj, so they still represented a considerable power.

It is interesting that the Dravidians were

fighting alongside the Kushans and later on the Hephtalites, and they have

never forgotten - even today — the well-known fact that the Arians defeated

them several thousand years ago. The existing Hun centers are proven by the

Gaonri Epitaph from 955 C.E, found in the village of Vanika near Indore.

Besides this, it is well known that the Hun princesses married some Rajasthani

rulers and even other Indian princes, too; e.g. in 977 C.E, the Medapata ruler,

Allata, married Hariyadevi, the daughter of a "Huna Mandala" king

proven by the Atpru Inscription. The princess established a town in Mewar -

today the eastern part of Rajasthan - where several Hun villages still exist

with the following names: Hunavasa, Hunaganva Hunajunmu, Madarya, Kemri.

Similarly written documents show that, in 1009, the Chalukiya ruler,

Hemachandra, had to fight a Hun prince for a princess in a marriage-contest.

The Hun prince was his rival. In 1072, the Khaira Tablets prove that the

Kalachuri clan's queen was a Hun ruler's daughter. In 1153, the Inscription of

Ajmer proves that, a Hun royal family was ruling in Ajmer. So it shows that the

Huns were present in a huge part of India. This is due to the fact that

"in the veins of three prominent ethnic groups: the Rajputs, the Gurjars

and the jats, Hun blood is flowing in a substantial quantity."

The Huns remained in India for several hundred

years, settled down there and became Indians. Some leading tribes of Rajasthan

originated from the ruling group of the Huns and several other provinces were

even ruled by them. The Gurjars arrived with the Hephtalites in the fifth

century; they were shepherds, but actually they supplied the food provisions

for the Hun army. In India, they also became shepherds and the Indian society

accepted them as Kshatriyas - the second caste - and, thus they were called "the

royal shepherds". The Jat tribe originated from the mixture of the Hun

soldiers and the local population and later on they became the famous, brave

fighters, the Sikhs. How did the despised mlecchas (foreigners, lower-caste)

become citizens of the second-caste? The Brahmins played a very important role

in Indian society and, by the end of the 7th century they realized that the

brave Hun soldiers had adopted the Indian customs and religion - primarily

Shaivism - and, by intermarriage with the wise Aryans, they became useful to

Indian society. For this reason, at the end of the 7th century, in Mount Abu -

at that time it was called Arbuda - the Rajput clan volunteered for the

so-called "ordeal by fire"; the Brahmins were present at the test.

Later, they spread the news that a mythological bird had risen up from the fire

and this bird took the ancestors of the Rajputs to the plain, where they were

purified from their foreign origin and they became second-caste members of

society; in this way they could be elected as kings. This is naturally a nice

story of the Brahmins and it shows that even they accepted them and legalized

the descendants of their former enemy.

It was a custom in India for foreign conquerors,

in time, to be assimilated into the Indian society but they were always

assigned to a caste according to their professions. For instance, the members

of only one foreign tribe became Brahmins, the so called magars, who came from

Iran, or from other sources the magars, who had arrived together with

Mihirakula, as the priests of the Sun God and Sun worship.

After this, the Rajputs fought bravely in the

Middle Ages against the Muslim conquerors who had never succeeded in occupying

the whole of Rajasthan, because, from the fortified castles, the mobile defense

troops rode here and there and, by the time the Muslims had occupied one

castle, they moved on to another one.

Apart from the Rajput soldiers, the Rajput women

showed an example of ideal morals and heroism. Even today Rajasthan state is

the most interesting, most colorful part of India, culturally too, and it is

curious that the people do not have any Aryan features. Their clothes also

preserve the traditions of Central Asia: the men wear tight trousers, white

shirts with loose sleeves and dark colored waistcoats - similar to the Csángó

(today in Rumania, an old Hungarian tribe) and the Szekler national dress. The

only difference is that the Rajasthani men wear turbans, but this is due to the

hot climate. Their folk art and music expressively indicate their Central Asian

origin. On the wall near the Maharana's palace gate in Udaipur - the present

capital of Mewar - a huge painting is visible: a Rajput warrior on horseback,

with the stirrup, which is a Hun invention. Indeed, all the decorations in the

palace: the peacock, the tree of life and the palmettos, are familiar to

Hungarians. When the Maharana (this title means that he is the spiritual leader

of all Rajput maharajas - and it corresponds to the ancient name, Maharajadiraja)

succeeded to the throne, he made a compact, sealed with blood with his old

ally, the headman of the Bhil tribe, then made a deep bow toward the East and

rode on horseback through the eastern gate to their ancient, sacred temple:

Eklingji where the priests consecrated him. Their ancient goddess was Mataji

and their god was Surya, the Sun God. So many relationships with the

Hungarians!

Now let us see what happened to those groups of

Hephtalites who did not want to assimilate into Indian society or who did not

rule in Kashmir but went further to the north to Bactria, toward their original

land in the Oxus Valley. Their former enemies, the Sassanians, did not forget

their defeat and, after winning a battle against the Parthian army, they

started a war against the Hephtalites in Bactria and in the Bokhara area. In

565, they defeated the Hephtalites. In the meantime, the former vassals of the

Hephtalites, the Türks, became strong in the Oxus Valley and in Tokharistan,

and they wanted to take revenge upon their former masters. They won a battle

against the Hephtalites and then they wanted to put the White Huns in a vassal

status, claiming tribute from them. The kagan, the armed forces and the leaders

naturally were forced to flee. They were joined by a part of the Zhuan-Zhuan

tribe, who were also fleeing from the Turkic army. Although they were opponents

of the Hsiung-nus in ancient times, in 565 C.E. the common fate forced them

together. Among these tribes, there were the so-called Uar-Huns, or according

to other sources, the Var-Huns, who were called Avars later on. The Indian

sources mention that, in the Caucasus, they were joined by some other Avar

tribes that had settled down there earlier. Some Indian scholars state that

these tribes must have been the descendants of Atilla. In any case, the

Hephtalite army with the peoples who joined them, marched toward Byzantium, at

a great speed, pursued by the Türks. In 568 C.E. the Byzantine sources write

about them, mentioning the name of their commander, Bavan kagan. The history of

the Avars in the Carpathian Basin is well known, I have dealt with the history

of the White Huns primarily because they are Hungarian ancestors through the

Avars, Actually, the Hungarians are the descendants of the Huns by two direct

lines.

Great👍👍सही इतिहास बताने कज लिए

ReplyDelete